How Signal's design contributed to the U.S. war plans leak

A product incident review

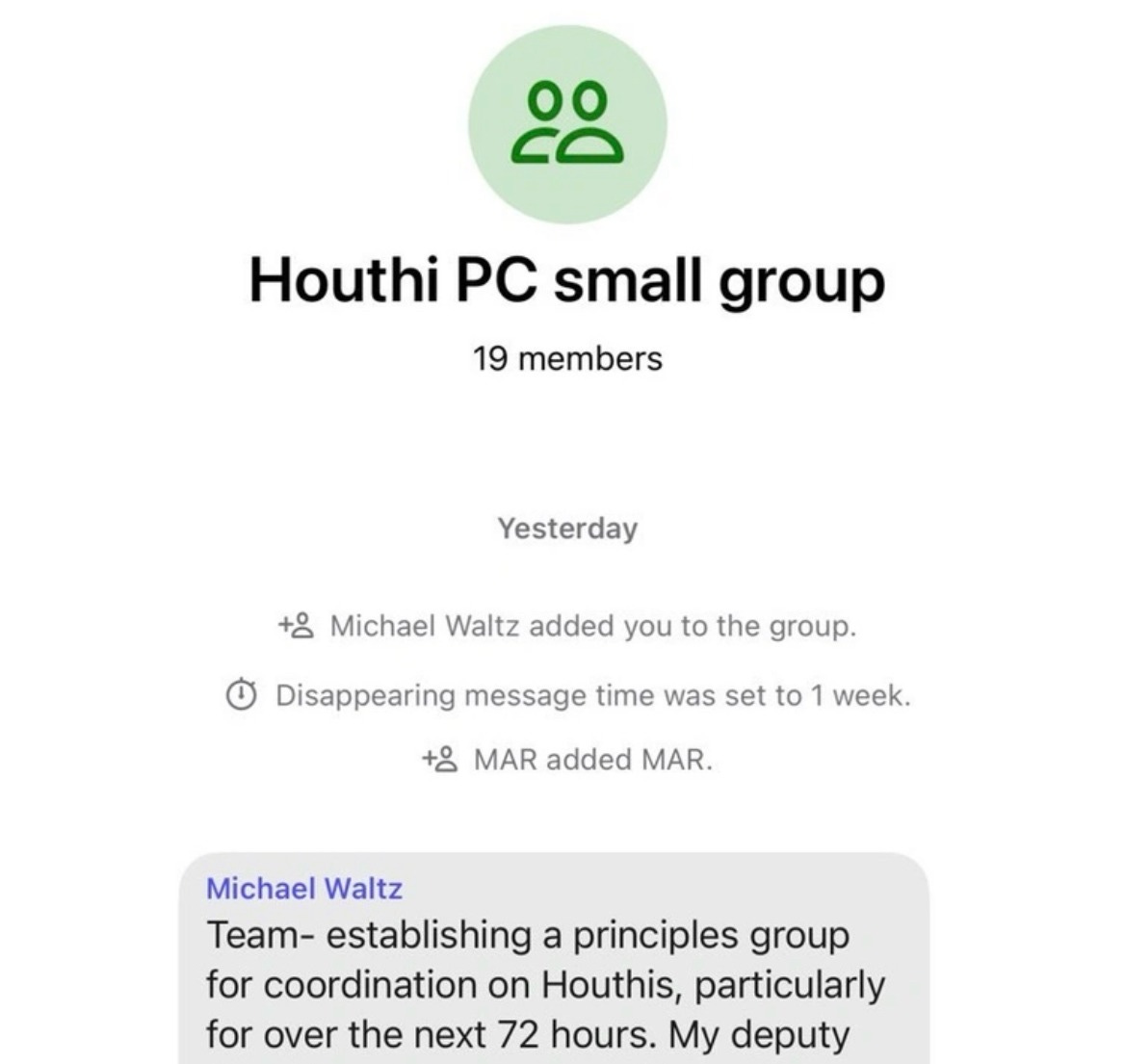

On March 13, as the U.S. prepared to bomb the Houthis in Yemen, National Security Advisor Mike Waltz mistakenly added The Atlantic’s Jeffrey Goldberg to a Signal chat. This went unnoticed by Mike and everybody else in the chat as the outlines of attack plans were revealed and debated.

But as Don Norman points out in The Design of Everyday Things:

The idea that a person is at fault when something goes wrong is deeply entrenched in society. That’s why we blame others and even ourselves… But in my experience, human error usually is a result of poor design: it should be called system error. Humans err continually; it is an intrinsic part of our nature. System design should take this into account.

Here, we could blame the chat group for (a) using Signal in the first place and (b) the actual flub where Mr. Waltz added the wrong user.

Maybe better to blame the government itself, which is a system, too. We can and should hold it accountable for securing its messaging, whether that means holding its people accountable or improving its own secure apps.

But this post is about the Signal side.

Product designers don’t have the luxury of blaming their users, especially regarding privacy and security. For example, we now know that users can’t be trusted not to re-use passwords, so we have password managers, passkeys, and two-factor authentication. And companies that text users one-time codes now routinely warn users not to share those codes to make them more suspicious of scams. Signal, for example, appends a warning: “SIGNAL: Your code is 123456. Do not share this code.” This case is no different.

After big blowups like this, companies hold “incident reviews.” The good companies embrace Don Norman’s ethos, performing root cause analyses and learning how they could better serve their users in the future. These post-mortems must be thoughtful and forward-looking despite the firestorm—perhaps especially difficult when likely half the employees hate the administration these users represent.

I wanted to do my own armchair incident review, not to shame Signal, who I don’t think has done anything unreasonable, but to shine a light on product usability and why it matters as much as technical standards and underlying cryptographic protocols. I was pretty sure I’d find some gaps, and indeed, I learned some interesting things!

Note that I’m not a privacy or security expert. I’m a product manager with a long engineering background. I’m new to Signal—hopefully, being fresh-eyed gave me a leg up in finding usability gaps.

What we know

Mike Waltz added Jeffrey Goldberg to the chat here, as these screenshots from Mr. Goldberg’s perspective show:

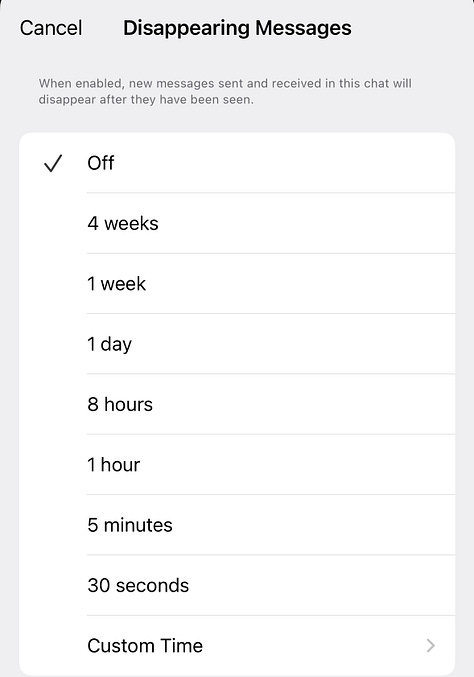

He signaled his intent for the group to contain sensitive info by turning on disappearing messages. The chat continued for pages and pages without anybody noticing that a journalist was there. Here’s an example:

The rabbit hole goes deeper, beyond Signal to Apple iMessage. The White House recently claimed that Mr. Waltz had, in fact, clicked to add Brian Hughes to the chat. However, earlier, Mr. Hughes had texted Mr. Goldberg’s number to Mr. Waltz, and Siri auto-suggested an iPhone contact merge, thinking it was a new number for Hughes. My read is that Waltz mistakenly accepted the suggestion. Since Signal’s primary user key is based on phone numbers, Mr. Goldberg entered into the chat.

This explanation seems plausible to me, so I’ll run with it.

The use case under review

I wanted to know what flaws in the app led to this failure and what Signal could do about it.

But like everyone else, I wondered: Is Signal even appropriate for this scenario?

Let’s define the scenario as: “A large group chat in which sensitive information is shared with a trusted set of collaborators” and see how Signal stacks up.

Group privacy or user privacy?

I grew uneasy as I played around with the app, imagining myself in the Houthi PC Group chat. I looked over the screenshots shared by the Atlantic. Who were these people?

This list and the ease with which new members are added do not instill the confidence I need to feel safe discussing war plans.

Then, I learned that (similar to iMessage, but dissimilar to Slack or Messenger), everybody in the group has a different view of this contact list. You can only see somebody’s name by correlating them with the contacts on your phone.

That’s great for the privacy of individual users, but it’s pretty terrible for the privacy of the group’s communications if you don’t know who you’re talking to.

In our secure communication use case, members want to ensure they’re sharing only with people they trust and are entitled to the information, which means everyone should be aware of who’s in the chat.

Why did a bunch of educated professionals use Signal despite this? There’s speculation that they wanted to avoid government transparency standards.

But, spirit of Don Norman on my shoulder, I wanted to see if Signal made these tradeoffs clear. I wanted to check the product marketing.

The marketing

Signal’s first marketing line in Apple’s App Store is “Signal is a messaging app with privacy at its core.” If that’s true, why was there such a simple privacy leak?

Meanwhile, after the incident, they claimed on X that Signal remains the gold standard for private, secure communications.

The group vs individual privacy nuance is lost here. Unfortunately, I think it’s plausible that most of the (non-techie) people in the chat didn’t realize the risk they were taking.

It’s not uncommon for products to intentionally turn users off—think child-proof lids and hard hat warnings. One brilliant example is the euthanizing of the dog at the beginning of House of Cards, designed to repel viewers who weren’t going to like the show anyway before they would waste time and post bad reviews.

Perhaps more relevantly, Basecamp clearly markets itself to small and medium businesses, letting enterprises know they need not apply. Likewise, if Signal had somehow convinced the government not to use it, they would have avoided this headache.

Signal’s existing group privacy features

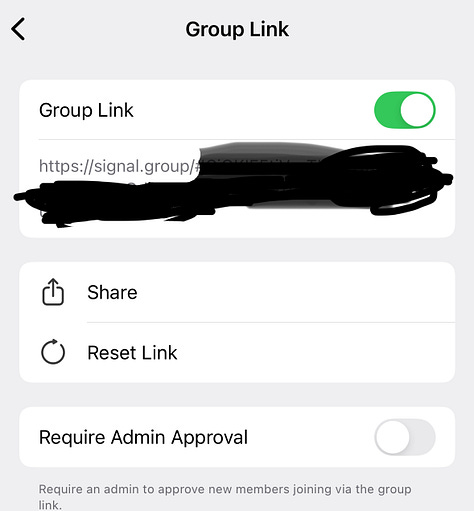

Signal has a hodgepodge of features for group privacy, including disappearing messages and two different ways for the admin to restrict who gets added. However, these features are scattered, and none of them is turned on by default—a prioritization of convenience over privacy.

It’s all too easy for an admin to miss something when locking down the group.

We know Mike Waltz, the admin, turned on disappearing messages. But he didn’t turn on “Only Admins” adds of members, given that MAR added MAR. (Marco Rubio—I guess he has two Signal accounts.)

How could Signal be better optimized for group privacy?

At this point, it just seemed like Signal doesn’t take group privacy that seriously. And it makes sense—they’re a free consumer app funded by individual donations, not a corporate app/cash cow. Still, it’s useful to imagine what they might do to expand into that use case. Some of these are probably doable. Others represent a larger pivot.

Let admins express their privacy preferences

One idea is to use an oft-overlooked design technique: ask each user what they want.

Imagine if the group admin could express their basic security and privacy posture upfront. Mr. Waltz would have been presented with two choices when going through a group creation wizard:

If he clicked the former, this would activate a number of changes to defaults (which could still be customized as usual):

Admin approvals would be required by default for adds and Group Links.

Disappearing messages would default to something reasonable, or he would be prompted whether to set them up in the next step.

It could also turn on a number of features designed to verify chat members, discussed below.

Some of these changes would be too intrusive for Signal’s privacy-conscious audience to be turned on by default, but letting individual chats opt into it might tighten privacy for a self-selected set of users without burdening and pissing off the rest. And learning about the intent of your users is a great way to make good default choices on their behalf.

Two-person approvals

Anybody in the group chat could have mistakenly added somebody, and nobody would have noticed. This is a big fat “OR” problem because any one of the nineteen members could make a mistake. The larger the group, the bigger the problem.

Admins are humans too, so simply restricting adds to them wasn’t enough, as Mr. Waltz made clear when he added Mr. Goldberg.

How could Signal make privacy leaks into an “AND” problem where two or more users have to screw it up?

First, secure chat groups could require a second person, perhaps another admin, to review and OK any member addition.

But on what basis would the review happen? For that, they would need more user metadata.

Centralized account lists, more transparency

By inviting users from peoples’ personal contacts lists, Signal users implicitly trust everyone’s contacts. Mr. Waltz and Siri teamed up to mangle his contacts list, and that was enough to compromise this model. But it could also happen with a simple typo to a phone number.

Typically, companies collect and verify emails and store them centrally. Mr. Goldberg would have been flagged for not having a government email address.

Even if he got in the group, first and last names, along with profile pics, would help ensure that the other chat members know who they are talking to.

Signal is designed to get as little user metadata as possible, so I’m sure this would be a tough sell to the team.

But here’s what they’re giving up relative to Slack, who maintains centralized lists of users with verified details. If this chat were in Slack:

Mr. Waltz would have been warned as he tried to add Mr. Goldberg that he’s outside of his organization.

In the chat, all members would see this flag:

The Atlantic logo would also appear next to Mr. Goldberg’s icon.

That’s several layers of privacy protections! When you see how far an app purpose-built for this use case has gone with it, it becomes crystal clear how limited Signal is for private and sensitive group collaboration and how their emphasis on user privacy has led to that.

Could they balance group and user privacy without going so far the other way? Maybe. It feels like a tightrope walk, but here are a couple of ideas:

For starters, they could provide an account switcher that allows users to switch between anonymous and verified accounts without tying the two together.

They could take a page from Blind, who verifies corporate email addresses and then one-way encrypts them.

Takeaways

Stepping out of my design fantasy now. Managing lists of verified users would be an expensive pivot for Signal. Collecting verified data for specific upgraded secure chats would probably be a good way to do it, but my best guess is that they will not want to be seen as eroding their core promises not to collect data, which is still valuable for the reasons they’ve always stated.

However, an incident like this can provide conviction—certainty that it’s worth doing something, even if that thing seems hard. If not at Signal, perhaps at a competitor.

I don’t want to dunk on Signal. Design is like this—reasonable decisions made under tight constraints come back to bite. Really, I came here to celebrate how thoughtful design can overcome human error.

Thanks for reading. I hope I’ve channeled Don Norman well in leaving you with a bit more interest in design and a touch more empathy for us humans and our silly mistakes.

I’d love to hear from you. Though I understand this is a politically charged topic at a tumultuous time, please treat this as a nonpartisan space. I will take down any inappropriate comments.

Thanks much to Dmitry Petrashko and A. Nonymous for their feedback on drafts of this post.